On 9th January 2020 a number of people braved the seasonal weather to assemble in the Dark Island Hotel to hear Robin Sutton’s talk about the Yorkshire Dales. We were treated to a full range of seasons, but on a breezy January night it was good to see a lot of pictures of the dales and their wildlife in summery weather.

Robin worked in the Dales at Malham Tarn Field Studies Centre for fourteen years, giving him a good opportunity to explore the area and record many aspects of its habitats and species in different seasons. He noted the importance of regularly recording common things, allowing observation of changes over time.

The Yorkshire Dales lie between the Pennine hills that form the watershed between east and west in northern England, so some rivers flow into the North Sea and some eventually into the Irish Sea. The dales are glacial valleys: the typical U shape with flat bottom and steep sides, cut into the hills which are composed of alternate layers of hard sandstone and limestone, the sandstone on top of the peaks and the layers of limestone increasing in thickness on the lower slopes and valley bottoms. The highest ‘Three Peaks’ are well known: Whernside [possibly named from the use of sandstone for querns], Ingleborough [the fort of the Angles] and Pen y Ghent [Hill of the Wind]. The limestone has horizontal bedding planes formed as the sediment was laid down, and vertical breaks or joints; while the stone itself is impermeable, water can travel along these joints. In some areas there are expanses of limestone with an uneven but overall bare level surface broken into segments or ‘clints’ by deep clefts or ‘grikes’ which follow lines of joints, forming a ‘limestone pavement’. In the clefts, with shelter from winds and grazing animals, vegetation grows, including woodland species; if stock were excluded soils would gradually develop and the whole area become a woodland.

Robin took us on a circular ramble in the Malham Tarn area, showing different types of vegetation and some typical and some unique species on the way. For instance, Malham Tarn is home to a flightless caddis fly which occurs nowhere else in Britain, but is also known from Estonia! Plants occurring in the area include Bloody Cranesbill, Rock Rose, Birds Foot Trefoil which supports the Common Blue Butterfly, Early Purple Orchids [some of which are white] which attracts queen bees although the orchids produce no nectar. In early summer a lot of the flowers are yellow: Ladies’ Bedstraw, Yellow Rattle, Cowslips; and later in summer blue is more dominanat: Harebell, Small Scabious and Devil’s Bit Scabious and Hard heads, attracting Painted Ladies, Red Admirals and Dark Green Fritillaries, Chequered Skipper and Brown Argus among other things.

The area has a range of soils from the calcareous on the limestone to more acid where there are areas of boulder clay formed during the glacial period and some acid peaty areas. In the limestone areas there are ‘shake holes’ which have formed when water running down joints in the rock has eroded the rock under the surface until a cavity is formed and at some point the uppermost rock with the topsoil drops down; these can be a hazard to visitors.

As water is diverted from the surface down sink holes to channels under the rock, dry valleys form, but in very heavy rain the underground channels can be filled and the valleys run again with surface streams. At some time in the past the cliff at Malham Cove was formed, but water very rarely comes over it now: Robin did not see water falling there during his years living there but was told that during Storm Desmond in 2015 so much rain fell that water did come over, forming the highest waterfall in Britain. There are dark areas on the rock face looking like soot. When Charles Kingsley visited the area and saw this it may have inspired elements of his ‘Water Babies’.

Peaty areas are formed where water loving plants grow in wet areas and gradually accumulate a growth of peaty material which as it rises above the water table supports such plants Lesser Clubmoss, Cotton Grass and Cross leaved Heath, the very pretty Grass of Parnassus and the Birds Eye Primrose which grows only in the north of England.

There are also areas of woodland with Ash, and expanses of Wild Garlic, Bluebells, Red Campion, and Sweet Cicely, which was brought by the Romans who chewed the stems.

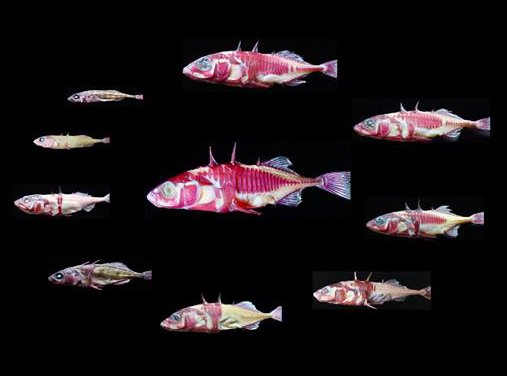

In Malham Tarn itself there used to be crayfish, which may have been eradicated by a crayfish disease, as there are none now apart from in a very small area of the tarn, close to an area of yew, giving rise to the theory that chemicals from the yew, leaching into the water, may provide some protection to the crayfish in that area of water.

Robin had all sorts of intriguing little facts about the area, plants and animals, which added to the interest of his talk. His illustrations were excellent.

The next talk will be: Geese, Peat and Malt Whisky: Islay by Martyn Jamieson on 13th February at the Dark Island Hotel, 7.30pm