On Thursday 8th Novemeber 2018 a small group assembled in the Dark Island Hotel to hear Carl Smith speaking on ‘North Uist – the Scottish Galapagos: a hotspot of stickleback biodiversity’, a talk organised by Martyn Jamieson for Curracag, but open to anyone interested.

Those of us with any familiarity with North Uist are well aware of the numerous lochs scattered across the island in the range of local habitats: moorland and peat bog, machair and the blacklands, and the lagoons in which the salinity can vary from almost marine to practically freshwater, depending on rainfall, tides and spray. Few of us will have realised that these support an extraordinary range of forms of the three-spined stickleback – and that the Queen Charlotte Islands off the west coast of Canada are the only other area in the world known to have a similar diversity of sticklebacks, though there is no suggestion that there is any connection between the two populations – they have developed their differences independently.

Carl Smith, a reader at the University of St Andrews, has been studying sticklebacks for twenty–five years, including ten years in North Uist.

Our sticklebacks will have arrived in the islands only after the last glaciation which covered the islands so 15,000 years ago or less. Probably marine sticklebacks were stranded in freshwater systems or entered them as sea levels changed after the glaciers melted.

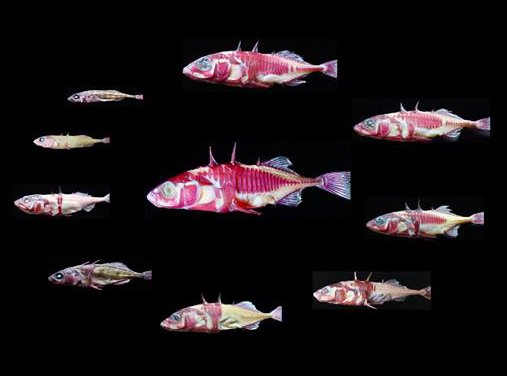

Marine three-spined sticklebacks are nearly 3” [7cm] long, have three spines on their backs, bony plates on the sides of the body and fins in the pelvic area with spines that can be locked in place, so small but well protected. In the lochs of North Uist the same fish takes various forms, from something very close to a marine type to a much smaller creature about half the size of the marine form, with no spines, no bony plates and no pelvic fins or spines. There are intermediate forms with varying sizes of spines, areas of plates and pelvic fins or not. One gene controls the differences in the plate formation.

The semi-saline lochs have fish close to the marine type; the machair loch fish range between those with medium protection and those with little, and the peatland lochs contain a range of fish with some plates to those that are completely defenceless and small. Low levels of calcium in these lochs may partially explain the lack of bony features, though other kinds of fish manage to extract enough calcium from their environment to grow normally.

Trout, together with birds and eels, are great predators of three-spined sticklebacks; trying to assess predator levels in lochs led to Carl Smith and his teams fishing a range of lochs with special flies made to look like three-spined sticklebacks, and the conclusion that predator numbers did not explain the presence of small defenceless fish. At present he is working on another explanation as to why there should be so many different forms of these fish.

How does North Uist compare with the Galapagos? One species of finch arrived there about 5 million years ago and over time their descendants have adapted to the different habitats and food sources on the islands in the archipelago, and developed into different forms now recognised as fourteen distinct species. It looks as though the North Uist sticklebacks might be undergoing the same process, but much more rapidly. Whether the tiny defenceless form found in some lochs can really be regarded as the same species as the stoutly armour-plated and spined fish in the sea and lagoons is debateable – but there are all the forms in between.

Dr Smith kindly answered numerous questions and there was some interesting discussion following his fascinating talk. One point of some concern is that other researchers are interested in the North Uist sticklebacks and specimens are in demand. The numbers of the different types in the different lochs are unknown, so whether they might be endangered by over collecting is also unknown. In some lochs there may also be a detrimental effect from, for instance, run-off from application of agricultural fertilisers on the adjacent ground or close to feeder streams, or the presence of fish farms with associated nutrients and build up of fish faeces.

So far the lochs of Benbecula and South Uist seem not to have attracted the same attention; perhaps they also support a diversity of three-spined sticklebacks.

Dr Smith has contributed a paper to the latest volume of the ‘Hebridean Naturalist’, available through the Curracag website, so anyone seeking an authoritative account should look there!